A national diet crisis

Around two thirds of people are overweight or obese in the UK and diet-related diseases, such as cancers, heart disease and stroke are the major killers. The advice about what people should be eating for a healthy diet has remained consistent over the past few decades: eat plenty of fruit and vegetables and watch the amount of fat, sugar and salt that you eat.

The research that Which? has conducted over the years shows that most people know what makes up a healthy diet, but struggle to put this into practice. There are a variety of reasons that are raised from the price of healthy vs less healthy foods, convenience to confusion over levels of fat, sugar and salt levels in food.

Tackling the barriers to healthier eating

As the UK’s leading independent consumer organisation, we have campaigned to tackle the barriers to healthy eating. This has included tackling misleading health claims on products, ensuring more responsible marketing to children and clearer nutrition information.

Nutrition information has been provided on food products in the UK for many years. Although the provision of nutrition information only became mandatory under EU legislation recently, many supermarkets and manufacturers have voluntarily provided this information.

An important issue has always been how consumers interpret this information – and whether it is easy enough for them to use. Some supermarkets have included guidance levels on their own-brand products for a number of years to help consumers work out whether a product containing 20g fat, for example, is a lot of fat or not. But with nutrition information just on the back of pack, many consumers did not use it – either because it was too complicated or they simply did not have time when dashing around the supermarket.

Simple front of pack labelling

Over the past decade, attention has therefore focused around providing simple front of pack nutrition information in addition to the nutrition information on the back of pack. The problems of poor diet in the UK meant that a clearer system of nutrition labelling that most consumers could easily understand was needed.

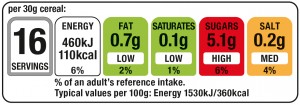

Which? carried out consumer research testing different labelling formats, as did the UK’s Food Standards Agency. This research showed that it was most useful to have a scheme that gave a clear indication of whether the levels of fat, saturated fat, sugar and salt were high, medium or low in a product using colour coding.

With consumers eating a lot of processed foods where the nutrition content may not be obvious, it was important to be able to give people a quick indication without them having to carefully examine each product label. The research also showed that schemes that only highlighted ‘healthier’ options were unlikely to work so well as they rely on people already being motivated to be healthy. By showing whether nutrient levels are high, medium or low, consumers can make a judgement about the nutritional content across products and decide how regularly they want to buy them and how much of them they want to eat.

Supermarket support

The colour coded labelling scheme first started appearing on supermarket own brand products in 2006. The supermarkets that used the scheme based it on criteria set down by the Food Standards Agency. This determined thresholds for how much fat, saturated fat, sugar and salt were ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ based on reference intakes determined from the population dietary goals set by the government. The nutrients were chosen because they are the ones of most public health significance in the UK. Average salt intakes are, for example, much higher than the recommended daily intakes and linked to rates of stroke. Many people eat too much fat and sugar, potentially increasing their risk of heart disease or leading to excessive weight gain.

The scheme appeared in several different formats. Some smaller manufacturers started to use the scheme as well as the supermarkets on their own brand products, but the main manufacturers opted for a different scheme, showing the levels of the nutrients as a percentage of the guideline daily amount. Some supermarkets went for a combination of both schemes – so that consumers had information about the amount per portion as a percentage of the guideline amount, as well as colour coding of the levels.

Improving consistency

The review of nutrition labelling at EU level as part of the EU’s Food Information Regulations prompted a review of these schemes. Consumer and health groups strongly supported the colour coding scheme, but were concerned that the inconsistent front of pack labelling schemes were failing to make choices simpler for consumers.

Once the EU requirements were agreed, with basic legal requirements specified and the option for national schemes to provide additional forms of expression, the UK government consulted on what would be the best approach.

In August 2012, Tesco, the largest UK supermarket announced that it would start to use colour coding on its own brand products. This prompted all of the supermarkets who had not previously been using the colour coding to say that they would voluntarily use it too.

The UK’s Health Department reviewed the criteria for colour coding to bring it in line with the EU Food Information Requirements. The British Retail Consortium, representing the supermarkets, also developed guidance on the format of the scheme, ensuring consistency as well as some flexibility for branding.

The UK voluntary scheme

In June 2013, the new criteria were published. As well as the supermarkets who said that they would be using the scheme, some manufacturers including Nestle, Mars and Pepsico said that they would start to use the scheme on a voluntary basis too. They will be applying the scheme to the products over the next few months.

Which? has strongly supported this move. For the first time, consumers will have consistent nutrition labelling on front of pack across a wide range of products. More detailed nutrition information will still be available for those who need it on the back of pack. This should mean that people can make far more informed choices about what they eat and watch how many products high in fat, sugar and salt they eat. The scheme is not about stopping people eating certain foods, but about helping them to eat a balanced range of products. It also has the advantage of encouraging manufacturers to offer consumers a wider range of healthier options.

More informed choices

By the end of the year, we expect to see the colour coded labels on many more supermarket own brand products. Some manufacturers will use them, but many of the main brands have not committed to do this. While own brand breakfast cereals will clearly show the levels of sugar and salt they contain, for example, the branded products sitting next to them on the shelves will not. We therefore want to see more companies volunteering to use the scheme so that consumers can make more informed choices and ultimately be able to eat a healthier mix of foods.

Nutrition labelling on its own will not stop the rise in diet-related disease among the EU population and ease the increasing burden on our health systems. But simple, at a glance, schemes like this voluntary approach in the UK, will make some difference in helping people to make better choices.